As a writer of books set in the nineteenth century I’ve often found myself wondering what my characters should be eating. This has led me down all kinds of avenues of research and inquiry, frequently resulting in my becoming quite hungry! Or occasionally nauseated, because tastes have definitely changed in the last 140-150 years since the days of my books.

One of the most obvious changes has been the rise of vegetarianism and veganism into the mainstream. There were many Victorians who advocated a meat-free diet—in Britain the Vegetarian Society was formed in 1847 and the first American vegetarian cookbook was published in 1835. Yet the Western diet was primarily meat-based, and most Victorians would have been looking to get more meat protein into their diets, not less. Food absorbed a higher proportion of the ordinary household budget than it does today, and meat protein would have been comparatively more expensive for anyone who didn’t live in close proximity to a farm. So being able to eat plenty of meat was seen as an advantage by most people.

In addition, no nineteenth-century man or woman wanted to look thin. In 1878, a Chicago doctor called Thomas Duncan wrote the following in a book entitled How to be Plump:

“The importance of fat are [sic] physical, mental and moral. A child well nourished, fat and fair, grows rapidly and develops easily and finely; while a child thin in flesh (fat) grows feebly and develops poorly and with a struggle. A feeble girl or boy is almost certain to develop early and prematurely, and like premature fruit early and easily decays. The organs are poorly nourished, there is no fat in the abdomen and the form bends and contracts as in old age, while the fleshy body stands nobly erect and has a royal mien. In the lean, the functions are performed with difficulty; the digestion is feebly performed; friction is manifest everywhere and there is often explosions of the nervous system, i.e., spasm, neuralgia, or bursts of passion.

The lean are restless and irritable in mind, rarely contented, never quiet, they form the complaining element of society, and are unstable as a nation.”

In those days, therefore, following a diet was more about improving health than losing pounds. The ideal diet was rich in “nourishing” proteins, often with filling accompaniments like breads or puddings—useful if there wasn’t enough meat. Cooked vegetables and salads were served, but we should remember that for most people, vegetables—and some meats—had to be seasonal as there wasn’t the international supply chain we now know.

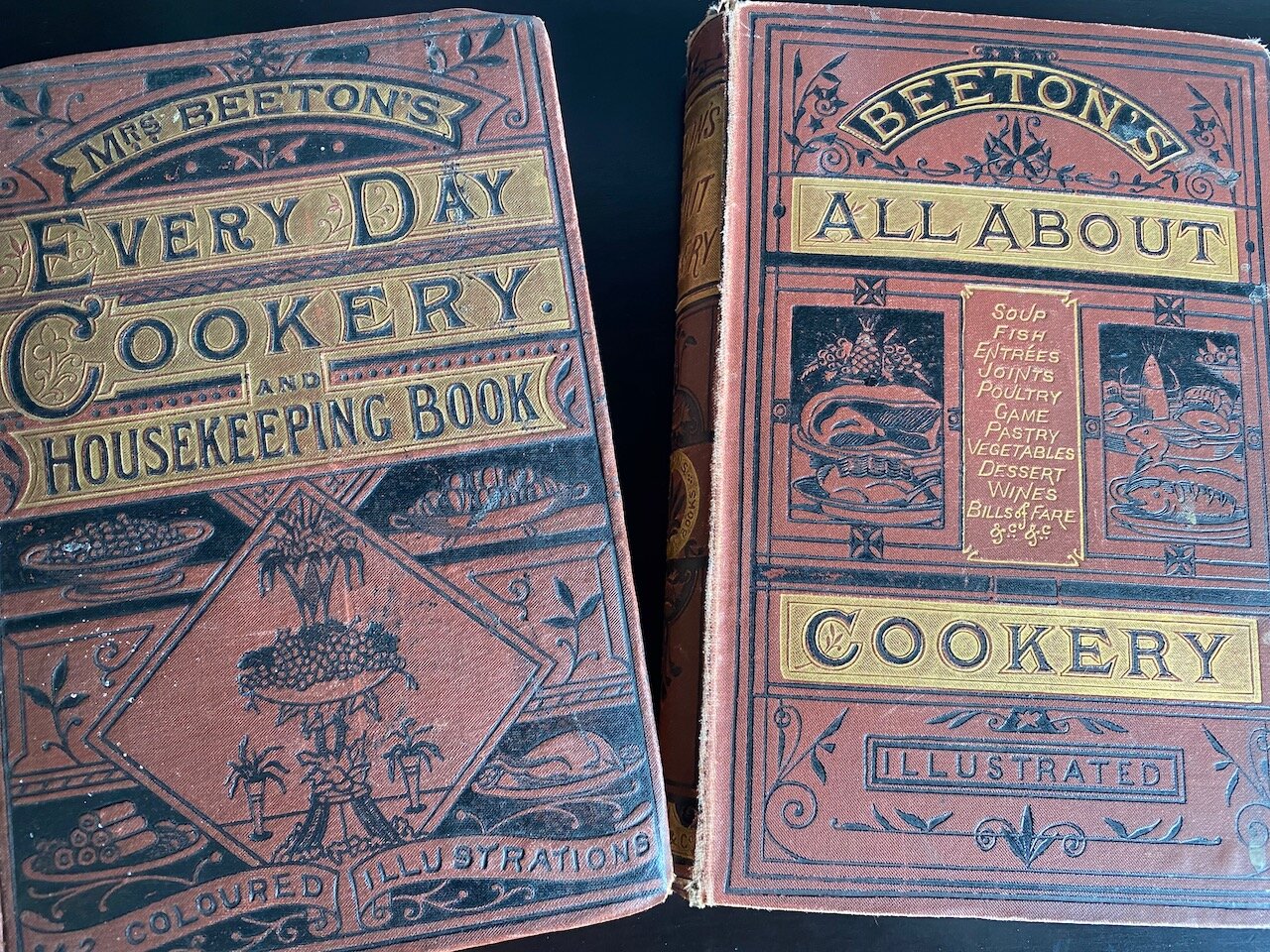

So how do we know what people were eating? My favorite reference books are the ones pictured above, both from the extensive series of Mrs. Beeton’s books that were published well into the twentieth century.

Isabella Beeton didn’t write most of them—in fact, having seen her first famous book published in 1861 it’s quite impossible that she wrote anything after 1865. In that year she died of childbed fever, aged only 28, after having given birth to four children, two of whom died in infancy, and enduring several miscarriages. The next year her husband sold the rights to her books and name to a London publisher, which went on to make a fortune out of books published under Mrs. Beeton’s name. They let the public believe she was still alive and dispensing advice and recipes!

I found one of the books locally and the other online, and they are a mine of information. They’re both from somewhere around the late 1870s or early 1880s, so absolutely spot on for the period I’m writing my series in. I could get lost in them, truly—they’re far more than recipe books, giving advice on the tasks of servants, foods in season, how to arrange the table for dinner parties and loads of other wonderful information. Even the copious advertising (about one-fifth of All About Cookery) is useful to me.

I’ll leave you with a taste of the 1880s by copying out the bill of fare for a June dinner for twelve guests:

First course—Green-pea soup; rice soup; salmon and lobster sauce; trout à la Genévése; whitebait.

Entrées—Lamb cutlets and cucumbers; fricasseed chicken; stewed veal and peas; lobster rissoles.

Second course—Roast quarter of lamb and spinach; filet de boeuf à la Jardinière; boiled fowls; braised shoulder of lamb; tongue; vegetables.

Third course—Goslings; ducklings; Nesselrode pudding; Charlotte à la Parisienne; gooseberry tartlets; strawberry cream; raspberry-and-currant tart; custards; dessert and ices.

In case you’re wondering, Nesselrode pudding is a frozen sweet pudding made with chestnuts. I had to go to the internet to discover that Charlotte à la Parisienne was renamed Charlotte Russe when its creator went to work for the Tsar. Mrs. Beeton (or whoever actually wrote the recipe) seems to assume people know it’s the same thing . . .

One day I’ll make Charlotte Russe, which is a confection of sponge fingers, strawberries and cream. Hungry yet?